I’d like to start by saying that if you have even the slightest chance to see this show, please come back to this interview after you watch it. For instance, they are going on tour in Canada in January.

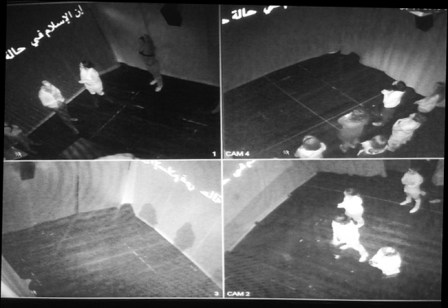

Foreign Radical by Theatre Conspiracy, the winner of Fringe First 2017, is an immersive performance, perhaps more accurately described as a twisted game with an obscure mechanic. Like many shows this year, it zeroes in on the current political and social climate. Many shows reflect on personal experiences of the artists or discuss the issue as a whole. This one pushes you to observe your immediate reactions to familiar questions about terrorism, surveillance and predictive profiling under the conditions of safe danger. I say “observe” because in the fast-paced narrative you are rarely given much time to consider your choices. In slightly over an hour you are taken back and forth in an ever evolving space, divided, interrogated, asked to work together, asked to compete, asked to assume power and give it up. I also got the chance to watch Foreign Radical from the tech box, where you see the entire crowd of 30 and and the performance space divided into four quadrants at all times through the security camera, which becomes a show in itself. Apart from being absolutely blown away by it on an emotional level, I was also dying to know what went into putting together something so clever and complex. How do you even conceive something so intricate, with so many variables and execute it so effortlessly?

The show is performed by Milton Lim as the Game Host and Aryo Khakpour as Hesam

I got the chance to chat to part of the Foreign Radical production team that brought the show to Edinburgh Fringe.

Vlada: I’m going to start with something really broad: what are the vital theatrical elements needed to create immediacy and intimacy of Foreign Radical?

Tim: We worked a lot on the size of the audience, especially once we got down to the idea of the four quadrants. We worked with a dozen people at certain times. Eventually we found that twenty was the golden number. Over the course of an hour and a quarter this people get to know each other rather well. That dynamic is really at the heart of it. Also I would say the divided audience, where some people are having a different experience and then discover throughout the show that they’re seeing something that others aren’t or doing something that others aren’t. I think that creates a really vital intellectual and active playful interest, which keeps people engaged.

David: In terms of dramaturgy, it’s important to connect the thematic elements to the actual pace of the piece. There are moments where the audience are forced by the nature of the questions to think and react very quickly and there are moments where they’re given a little bit more time to reflect and think. When you do that enough times and with the split of the groups, the dynamic that emerges between them becomes more immediate than anything that we could necessarily force on it.

Tim: Part of the game play element is the opportunity for people to speak and act. Everything they bring in becomes part of the material of the show. Often when people are leaving and I’m chatting with them outside after the show, they are not just talking about “what I thought” or “what my cerebral reaction was” but “here is what I did, here is what I said”.

Vlada: With Immersive Theatre the performance space needs to displace the audience away from real life. What kind of space did you want to create?

David: Often the decisions you make in a specific context are removed from the ultimate effect. Many decisions we make seemed really small and inconsequential, but may, in reality, have huge consequences. Also, decisions we make on the minute level can actually end up being in conflict with what we think our values are. So, from my point of view at least, part of the project was creating a space where all this dream like qualities allow you to dislocate your perception self, your decision making process.

Jeremy: I agree that it’s out of this world in a lot of ways, but also it mimics real-life situations. For example, queuing, being in groups or we’re meeting at a party or any other situation where there is a bunch of strangers that suddenly are interacting. There is also a lot of elements that evoke real life, which people recognise inherently. That’s not necessarily what we’re going for directly but that’s the ultimate effect. It’s pretty familiar to be in the queue or to step forward when your name is called out. The structure of the show evokes common physiological or somatic situations to find yourself in socially.

Jeremy: I agree that it’s out of this world in a lot of ways, but also it mimics real-life situations. For example, queuing, being in groups or we’re meeting at a party or any other situation where there is a bunch of strangers that suddenly are interacting. There is also a lot of elements that evoke real life, which people recognise inherently. That’s not necessarily what we’re going for directly but that’s the ultimate effect. It’s pretty familiar to be in the queue or to step forward when your name is called out. The structure of the show evokes common physiological or somatic situations to find yourself in socially.

Tim: You *points at Jeremy* also use the term mixed reality a lot.

Jeremy: Yes, it is, if anything, a mixed reality. Mixed reality theatres often attach more to uses of technology. I don’t know if our uses of technology are necessarily doing that. It’s more the kind of social situations we’re putting the technology in that contrast pretty heavily between drama, documentary and creating a heavy, tense atmosphere.

Vlada: You started devising the show in 2012 and premiered it in 2015. It’s gone through many iterations: you had it set in a shipping container, you changed the number of the audience members. There are also a lot of references to current political events. It’s a show that constantly evolves. Can you tell me about this process?

Tim: In 2012 I met Ron Diebert who is a global expert in cyber surveillance and Internet freedom. He runs The Citizen Lab at the University of Toronto. I went to a conference that he was involved in and did a lot of research over the course of maybe 9 months. Right after that conference the Edward Snowden revelation happened and the show became less about Cyber surveillance and more about… say, human rights. Also, racial profiling and those kind of ideas. Soon after Jeremy and David and I met in Toronto to talk about the concept, particularly in terms of space, an unusual space, an immersive space. After that, the project evolved maybe over the course of five or six workshops in the next year and a half, working with different spaces, always working with a test audience. Learning from the audience was a huge part of it.

Jeremy: At first we were working with an idea of having long, narrow corridors and a much bigger space. That was, design wise, very hard to achieve. The container offered that, in a way. It was actually two containers put together, maybe 44 feet or 50 feet long [13 – 15 meters. I looked that up for you, you are welcome]. We got to experiment with that design idea there. However, once we found the four rooms set up the project really took off. Also, the asking the audience different sets of questions was not a big part of the show at Your Kontinent [Media Festival], in the container iteration. As we continued working on the project, we really went further with that. Those two elements really brought together a lot of it.

David: One of the things that was there from the beginning was the evolving spaces that the audience can actually go into. So part of that corridor idea that Jeremy was talking about was that we were going to have the audience go down a single corridor in a group, get split up, go into different rooms, and each time they walked in or out of the room the room would be different so it would be a maze-like thing. That concept was actually there from the beginning, so everything we were testing from that point forward was basically a refinement of that, which was actually, production-wise, feasible, financially feasible. It was always about: ok, how are we going to split the audience, how are we going to create a sense of transformation of space, dislocation of space, and how is it that the audience can also come back and meet again in different ways having experienced the different spaces? That was basically there from the very beginning.

Vlada: You also changed Milton’s costume. In the early stages of show development it was a classic black tuxedo, but you changed it to a white suit.

Jeremy: It is another important element that we brought in. We watched a film, Confessions of a Dangerous Mind, which is a real story about a game show host that was also a CIA agent. His costuming and his character came into that. We were trying to find the character for the host for a long time. For a long time it was just Milton’s. Once we locked on this 70’s game show host feel, that’s where Kyla Gardiner took that costume. And it was white very largely because we wanted to maximise the light, we wanted it to reflect the light. But that was a really important aspect. The two earlier versions didn’t have this really colourful character of the game show host. Once we found that the contrast really kicked in. And I think that’s, again, touching to your second question, that’s where we were able to maximise that environment that brings people together, that brings the community together.

David: It allows him to remain evasive. He is a white canvas. It allows him to morph and change in different ways. Had he been a host in a black suit we have associations with that. That resembles a certain power dynamic, a certain power structure…

Tim: Class

David: Class, relationship to government establishment. But it was important to keep him in this fluid space where he can morph between any of those states.

Vlada: You very carefully create this balance between high-strung comedy and very profound suspense. That’s done largely through Hesam and the Game Host. Hesam is an essential part of that story, but the way in which he is developed, that’s unexpected. Then, the Game Host feels very alien to this story, and yet works brilliantly well. Tell me about creating those characters.

Tim: With Hesam, I remember, I just had a whole bunch of lines from news stories. So those early scenes, there was a lot of documentary in there. Not a lot from one particular story, but just lines collaged together. Then, Jeremy came up with the image for the first scene during a workshop and the characters started evolving from that, both on the level of the script and his identity. Then we talked about having really short, intense scenes maybe 6 month later. We just went back and forth on what those scenes might be, how it might build from… well… what is a torture scene that is not just a torture scene, you know?

Jeremy: Once the interaction with objects was developed as part of the show, it obviously required a lot of attention to who this character is. That also provoked all the discussions and questions about the details, which is still an ongoing conversation, because that really dictates way in which the audience will respond.

David: I will also add about Milton’s character – the Game Show Host. Once we understood that we have to have the dynamic of asking questions and answering them, there was a matter of who actually asks the questions and why. The thing about him being a gameshow host relates to the whole question of surveillance. In the world of surveillance is Milton actually the power, is he resembling somebody who is running the game, who’s in charge of the game, who’s directing all of this…?

Jeremy: …or a machine

David: …or is he a machine that grows and becomes larger than life behind the game that has its own trajectory, or is he just another character who positioned within the surveillance world and within the game he is indirectly, through some other entity, being put into conflict with all these other people? That’s also why his power position is constantly shifting. He is never really one thing or another, he never gets very serious, he is never really laughing, he is never completely in control, he never completely loses control, he is constantly somewhere in the middle. It’s connected to the way in which we relate to surveillance, because we don’t know who’s in charge of how it’s running but we are constantly interacting with it, constantly reacting to it. To me that was a big part of the conversation of defining Milton’s character as a Game Show Host. The thing about surveillance is that we fall into it because of conveniences and it is presented to us as a game. We participate on a small scale due to convenience through Google or all these other platforms. It’s a kind of game where we feel like we are getting a reward, which is what allows you to continue playing the game. You participate and you get a reward that makes you think that you are getting something more out of it, so you continue to do it. So he was also a really great vehicle to do that.

Vlada: What does this unlikely mix between all the genres that the show uses offer you?

Jeremy: The mood of the piece constantly changing and switching between intense images and humorous action allows us to manipulate different kinds of intimacy, to create different kinds of tension. I don’t mean only the dramatic elements but also relationship between the community that develops. For example, the audience get a chance to laugh together. That’s really important for getting that mix going, for getting people comfortable. Also, there is lot of dialogue and tension in the group to create extremities between the Hesam world and the dramatic world. I think, this is something unique to Foreign Radical: the very dramatic elements juxtaposed to the anti-theatre aspects of the piece. Bringing the two together really carved out those characters.

David: We needed to create a space in which we could mix comedy, drama and the game elements, without any of them seeming out of place, a narrative that moved fluidly between all these different elements.

Vlada: The constant changes in power dynamic are an important part of the show. Tell me about the structure of that, how that works with audience reactions and why you constructed it this way.

David: Well, in Foreign Radical, the thing about power directly relates to the question: does agency necessarily mean power, especially in a surveyed world? Just because you have agency to act in one moment does not mean you are in control and that applies to all the elements in the show. There are moments when the audience are given agency to act and then other times when they are not, and sometimes their agency results in something that they don’t necessarily think was going to be the result. Same with Milton’s character. So it’s about that power dynamic that is illicit. Sometimes we think we are in charge, we are making decisions that we understand the consequences of. And that’s not necessarily the case. It is also questioning where that power comes from.

David: Well, in Foreign Radical, the thing about power directly relates to the question: does agency necessarily mean power, especially in a surveyed world? Just because you have agency to act in one moment does not mean you are in control and that applies to all the elements in the show. There are moments when the audience are given agency to act and then other times when they are not, and sometimes their agency results in something that they don’t necessarily think was going to be the result. Same with Milton’s character. So it’s about that power dynamic that is illicit. Sometimes we think we are in charge, we are making decisions that we understand the consequences of. And that’s not necessarily the case. It is also questioning where that power comes from.

Tim: You choose to get on a plane and so you choose to get in a line and be searched, to have your luggage searched, to take your belt off, to take your shoes off. Where, really is the line of your power? It is your choice, but really your power is completely stripped away. We submit to that because we want to travel, so we justify that and we think that’s our agency, but really we don’t have power. Because ultimately in the game, in Foreign Radical, the audience is never in control. Absolutely not. There is just really no power, they have no power.

Vlada: When you are one of the audience in the show, you figure out very quickly that if you do certain things you are going to get something, you just don’t know if you want it or not. I know that you worked with videogame designers on developing the show, and there are clear links to that. How does the structure of rewards and incentives work in the show?

Tim: Kathleen Flaherty, our dramaturg, talked with videogame developers about how narrative is created in games and then put together a round table discussion where all of us talked about what crosses over between theatre making and game making. A term that I wasn’t familiar with came up through that: emergent narrative. It’s the idea that the narrative emerges through the action and that’s very different from show to show. We were working with it anyway, but that phrase, for me, became very useful.

David: When we were looking at videogame modelling, we understood very quickly what it is that makes someone want to continue playing the game – even if they are struggling or if they fail – is that at every step you are rewarded with something that gives you a moment of euphoria, however brief. And you don’t know what comes around the corner after that, but you want to keep going. So, there were two things that we tried to play with. The first one is that the humour element in the show helps achieve that, because quickly through the humour of the questions and because of the way it’s set up in the beginning the audience feel safe to some degree, which makes them more willing to participate, but then quickly when they understand that there are separate experiences happening depending on how they answer that in itself… the promise of a reward… Actually, it’s not a reward necessarily, because, like you said you don’t know if you actually want the thing that’s going to be given to you. But the promise of a reward is a very powerful tool to use and to motivate people with. The way we constructed it, you can’t really be strategic about it, as you don’t know what it is that you are going to get. You don’t know also if you get something, that means you miss out on something else. So, what it ends up creating, is forcing the audience to be honest. There is no built in, clear incentive to lying. There is no clear promise that if you lie or say certain things you are going to get something.

Jeremy: There is a naturalness in social interactions for people to tell the truth, which theynegotiate and ultimately submit to. Very few people lie in the game. It’s fascinating that they tell the truth. I mean, even still for me, playing the game… I’ve played it… however many times I’ve gone through it, I still have a hard time lying. It’s weird.

Vlada: Something I’ve noticed is a constant in immersive theatre productions is the transition walkway. It’s the moment where you walk into an imaginary space and the first image is one that helps you adjust, to submerge in that space. Your opening image is very powerful. Then, you also have the final sequence, which is yet another surprise in the show. So what is the significance of having that initial and final image? What does it do to the audience?

Jeremy: I think in a lot of way you answered the first part of that question already. That opening is about bringing people into a reality that they all know about but they’ve never seen. So that’s a real emersion in an absolute stark reality. And it’s definitely an opening entrance to the piece in terms of setting the mood. The ending is fascinating to us. We found that after our first preview going into our opening in 2015 and it’s ongoing in terms of discussion. It’s an anti-ending. It’s an ending that’s not an ending. It serves so many different purposes. Tonally it’s bringing us onto a wave of sort. So we are in this sea then suddenly we come through it, and we land and it’s off-putting, but it reverses roles in multiple ways. Tonally, personally for myself, I just love it. I love how it comes down and you land and you have another kind of swooosh down to an even calmer lake. We’ve always wanted it to be an installation environment and never really had the development time to take that further.

Tim: A couple of things to build on what Jeremy said. I feel now like functionally, as theaudience, we’ve been learning about each other a little bit more all the way through and the finale allows for a sense of real intimacy. It’s an opportunity to just be in the space together and it’s a signal about the show ultimately being about the audience, their experience, the dynamic that happened. So to come back and have a curtain call just didn’t really feel right. It leaves you in a moment of contemplation or the opportunity to socialise.

Vlada: Will Foreign Radical always be relevant?

Jeremy: I hope not.

Tim: Probably, as long as we want to keep doing the show, it will still be relevant. That’s an interesting thing about a show like this. Now, I like the influence that it has with audiences, the interested that’s generated, but it also comes out of these very heavy questions that have real stakes for a lot of people.

David: If history teaches us anything, then, sadly, yes.