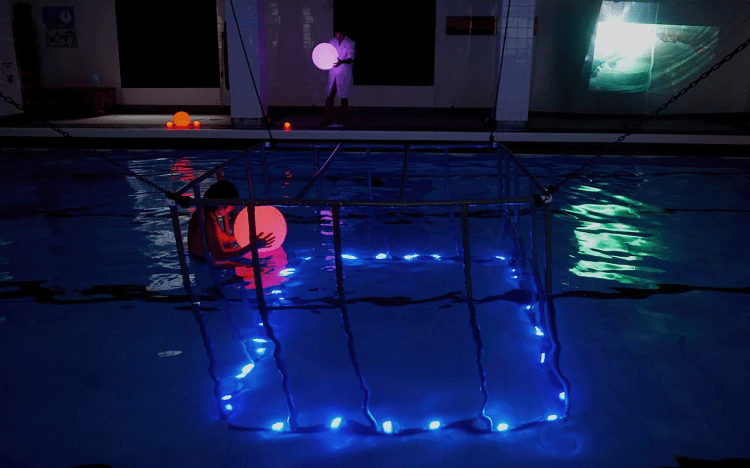

Brodsky Station is a performance that uses a swimming pool as a stage and the sound comes from a set of earphones every audience member is given. I know what you are thinking: “Something like this could never work as an effective performance, only as a gimmick.” And yet… I went to see Konstantin Kamenski’s play purely out of curiosity and discovered this ethereal dreamscape, which tells a profoundly moving story.

Brodsky Station was Kamenski’s graduate project for The Central School of Speech and Drama. His initial inspiration was “Victoria Station” by Herold Pinter. Eventually he moved far from that, developing a project with a separate text, which is based on Brodsky’s poetry, but still relates to some of Pintar’s ideas.

After the performance, Kamenski addressed his audience, sharing the news of Serebrennikov’s arrest, and asked them for a favour: to go home and look into this news story. And I thought, “I have to talk to this man.”

I was very lucky to get the chance to chat to him for a few hours, to discuss Russian theatre, the creation of Brodsky Station, censorship in theatres, and the place that performance art occupies in today’s world.

You studied in Russia and in the UK, and you have staged productions in both countries. However, from what I’ve seen from your work, it always has distinctively Russian themes, is written by Russian playwrights or features Russian actors. So, would you say you are a Russian director, a British director, or an international director?

Well, I would say I’ve always been and I will always stay a Russian director. I’m sure that my roots, my heritage is in Russian art, in Russian theatre. So wherever I go, I am a Russian director more than anything else. Whether I am staging a Russian play in English or staging any sort of new material, new writing or anything else: site specific performance, improvised theatre… It’s still related to Russia. Russia, Russian art, Russian themes. I find it fascinating because it’s… well, let’s call it a niche. Professional Russian theatre as we know it does not exist in the UK as such. There are some pieces of knowledge that British actors and British drama schools pick up, but nobody trains actors in the Russian technique. There are no professional Russian directors in the UK. So, it’s a niche and it’s my nature. I am lecturing at the Goldsmith University. I am reading lectures in Russian theatre. It’s a one-term course of lectures for BA Acting students. And I do understand, when I am talking to those students, how much the theatre of the 20th century was influenced by the Russian art. So I believe it’s a huge heritage and it’s undiscovered for the British audience, for the British professional theatrical circles. So I believe I am a Russian director. That is how I identify myself.

Has working abroad afforded you more of a sense of freedom in your work and more possibilities?

It’s not freedom as such, it’s an ability to find your place in the world. I started as a theatre practitioner in Russia. It was 2001 or 1999. I was running an independent theatre company. For five years in a row I’ve been making productions and I wasn’t able to find any support, governmental or commercial. Nothing at all. That was a probably just a period of time, later the situation changed. But at the time there was no place for independent theatre. The Russian theatrical system is developed so that there are academic theatres supported by the government, and if you don’t find your place within those it’s really hard to start as an emerging artist. I’ve graduated from the course of a director who was beyond this system, Roman Viktyuk. He’s now gained a lot of recognition, but until very recently, he was always out of the system. He was something else. He made abstract theatre, surrealistic theatre, absolutely out of the world of the classical realistic theatre, so he’s never been recognised much. This meant his students were unable to find a place within his theatre, simply because he was struggling himself. He was unable to provide us with some start commercially. So we went free and unprotected into the world and it was really hard to start. Academic theatres were unwilling to recognise us as directors at all. It was an absolutely different school from what they expected from young directors. So it was impossible to start. And I was exhausted, after 5 years I was exhausted. That’s why my theatrical career had a break. I moved to media production and TV production. I was exhausted and I did not see the picture to be honest. When I decided to come back to making theatre it was in the UK. I think I made the right decision. I went to the Royal Central School of Speech and drama and I joined what is probably the most competitive course. It was MA Advanced Theatre Practice. This course is designed so that we are introduced to working practitioners and they help us make the first steps. They even help us to establish the first contacts and help us build a network that we rely on as emerging artists. So with this course, I got into a system that really worked. A system that enables you to make a start. And I caught a wave. It’s a feeling like you are on a wave in the sea. You should work hard and do something every day, every day, make a small step on everyday basis and then it works. You make an effort and it gets supported. It’s just an amazing feeling when you make a production and it gets supported. You bring it to Fringe and next you are meeting a producer who is helping you make the next step or you are meeting an investor who is willing to invest just a little bit of money, but still it helps. The difference is the system did not exist in Russia, but it does exist in the UK. It’s not about freedom. A director is always free. Kiril Serebrennikov who’s just been imprisoned in Russia, he is free, he is free in his mind. If he is able to step out of his flat (he is under house arrest) and go to the rehearsal room, he will be working in exactly the same way as he was before the entire story started. He is free. In our minds we are always free. Otherwise, you would not go to the theatre, you would go somewhere else. So it’s about whether you are able to physically produce your work or not.

recognition, but until very recently, he was always out of the system. He was something else. He made abstract theatre, surrealistic theatre, absolutely out of the world of the classical realistic theatre, so he’s never been recognised much. This meant his students were unable to find a place within his theatre, simply because he was struggling himself. He was unable to provide us with some start commercially. So we went free and unprotected into the world and it was really hard to start. Academic theatres were unwilling to recognise us as directors at all. It was an absolutely different school from what they expected from young directors. So it was impossible to start. And I was exhausted, after 5 years I was exhausted. That’s why my theatrical career had a break. I moved to media production and TV production. I was exhausted and I did not see the picture to be honest. When I decided to come back to making theatre it was in the UK. I think I made the right decision. I went to the Royal Central School of Speech and drama and I joined what is probably the most competitive course. It was MA Advanced Theatre Practice. This course is designed so that we are introduced to working practitioners and they help us make the first steps. They even help us to establish the first contacts and help us build a network that we rely on as emerging artists. So with this course, I got into a system that really worked. A system that enables you to make a start. And I caught a wave. It’s a feeling like you are on a wave in the sea. You should work hard and do something every day, every day, make a small step on everyday basis and then it works. You make an effort and it gets supported. It’s just an amazing feeling when you make a production and it gets supported. You bring it to Fringe and next you are meeting a producer who is helping you make the next step or you are meeting an investor who is willing to invest just a little bit of money, but still it helps. The difference is the system did not exist in Russia, but it does exist in the UK. It’s not about freedom. A director is always free. Kiril Serebrennikov who’s just been imprisoned in Russia, he is free, he is free in his mind. If he is able to step out of his flat (he is under house arrest) and go to the rehearsal room, he will be working in exactly the same way as he was before the entire story started. He is free. In our minds we are always free. Otherwise, you would not go to the theatre, you would go somewhere else. So it’s about whether you are able to physically produce your work or not.

I also wanted to talk about your play, Brodky Station, specifically. You are not only a director, but also a video artist. From what I understand, all the projections, the glowing spheres, projection mapping – all of that you did yourself. I wanted to ask what do you think the use of multimedia adds to your exploration of Brodsky’s life and why have you chosen this very specific combination of staging techniques as the most effective way to tell this story?

With Brodsky Station, I feel that media is a partner for my actors. It’s another personality on stage. Because media is a part of our life and some people believe in media more than they believe in people. It’s more convincing, it’s more informative than anything else. So it’s not a design. When they call it video design, that’s not entirely true. It’s not set design either, because that exists as a tool to use. But media is a personality. I’ve been working in media for 13 years. I’m a very experienced content creator and editor. I am aware of everything that could be created in media, pretty much. If I don’t know how to do it, I know of the possibility of creating it, of the people I can go to, who can create it. If you are aware of something, you can include it into your creative world. So there is the freedom to choose between the tools and means of expression of your idea. When I was working with Brodsky Station material, I first found this water space. I did understand that this particular production should be in front of water. Because I needed a surface in order to get a reflection. Not even the water, I needed depth, a pit. At first I was trying to bring some water onto the stage. That’s technically absolutely impossible. The weight of water is technically impossible to fit onto the stage. And then at one moment I thought: “why I should bring water to the stage? I can bring the stage to the water. I can go to a swimming pool”. Not surprisingly, this idea came to me while I was doing the MA Advanced Theatre Practice course which affords this freedom of expression. We’ve been experimenting with spaces and watching other practitioners do it. I did also understand that I needed to create a videotape to express the ideas of one of the characters. So the video tape we are using is a compilation of images from the mind of the main character. Everything we can see is what comes to his mind. In this way, we are looking at the entire life of this person. We can see him recalling his entire life, his life in front of our life. That’s why I wanted video and it was rather hard to bring the hardware to the the swimming pool. Then LED lighting came because we needed something we could freely use in the water. Then, when we started having rehearsals in the actual swimming pool we realised that due to the acoustic conditions there we were unable to act live. The echo is so strong that you can’t really talk, you can’t deliver your lines. That’s how we came to the acoustic experiment. We recorded the entire performance, it’s in the headphones and there is no talking at all, no sound. It also helped us solve the riddle of providing both Russian and English languages, we recorded them in two different streams. So all the usage of equipment was based on some need and our demand to express a certain idea or the need to allow the audience to comprehend the entire story.

that this particular production should be in front of water. Because I needed a surface in order to get a reflection. Not even the water, I needed depth, a pit. At first I was trying to bring some water onto the stage. That’s technically absolutely impossible. The weight of water is technically impossible to fit onto the stage. And then at one moment I thought: “why I should bring water to the stage? I can bring the stage to the water. I can go to a swimming pool”. Not surprisingly, this idea came to me while I was doing the MA Advanced Theatre Practice course which affords this freedom of expression. We’ve been experimenting with spaces and watching other practitioners do it. I did also understand that I needed to create a videotape to express the ideas of one of the characters. So the video tape we are using is a compilation of images from the mind of the main character. Everything we can see is what comes to his mind. In this way, we are looking at the entire life of this person. We can see him recalling his entire life, his life in front of our life. That’s why I wanted video and it was rather hard to bring the hardware to the the swimming pool. Then LED lighting came because we needed something we could freely use in the water. Then, when we started having rehearsals in the actual swimming pool we realised that due to the acoustic conditions there we were unable to act live. The echo is so strong that you can’t really talk, you can’t deliver your lines. That’s how we came to the acoustic experiment. We recorded the entire performance, it’s in the headphones and there is no talking at all, no sound. It also helped us solve the riddle of providing both Russian and English languages, we recorded them in two different streams. So all the usage of equipment was based on some need and our demand to express a certain idea or the need to allow the audience to comprehend the entire story.

To me, possibly unintentionally, the fact that the sound was coming from the earphones added to the sense of isolation which, correct me if I’m wrong, is largely what the play is about.

Exactly, because when you are watching the actors who exist in some parallel space, what the actors have been physically doing is often not illustrating what you can hear. The plot is what you can hear. It’s a voice in your head. In a way that’s what happens with the main character, that’s what happens with that person at that moment in his life. He hears a voice and tries to identify where it’s coming from, who he is talking to him, what that person wants. And you can experience that as a member of the audience.

And when you first started working on Brodsky Station, did you conceive of it purely as an exploration of Brodsky’s life or did you want the play to appeal to broader themes?

It’s always a broader theme when we are talking about a poet in a country, which is imprisoning people of arts. So, Brodsky’s story of him being imprisoned for being a parasite for just being a poet without any education, that could happen at any moment, in any country where being different is a crime. So in a broad way it’s a story of a poet, not necessarily Joseph Brodsky. That is how many people understand it. So, it is not necessarily related to Brodsky, but to a person in those circumstances.

Do you think the ideas and the play have become more applicable in the light of recent events and theatre, I am tempted to say, “persecutions” in Russia?

I am more than sure about this. Not later than yesterday we, the entire 274 company,  went to the Royal Mile and we went a video recording we uploaded today on facebook. We were just expressing out opinion about what happened, about what was going on in Russia in support of Kiril Serebrennikov. Our actor, Oleg Sidorchik, who is a political refugee himself, he said: “we all remember the story from Brodsky’s persecution. He got sentenced to five years in labour camp. And Anna Akhmatova, a great Russian poet, said: “what a biography they are making out for our ginger guy!” In a way, all those persecutors are making out the biographies of the creative people in one way or another. History is designed, so the names of the persecutors go into nothing and the names of the artists who are being persecuted will be remembered forever. So, those people, who are investigating into Kiril Serebrennikov’s practice, they will be forgotten. Whatever they achieve, whatever the result is, they will be forgotten. Nobody remembers the names of Brodsky’s persecutors, but everybody remembers Brodsky. Same will happen to Kiril Sreberennikov. They can steal a few years of his life, yes they can. They can force him to go abroad, into immigration. Yes, he will be able to be a successful director in any country in Europe. He is a successful director in Europe. He already had very successful productions in Germany, and he could move there forever. People can leave, some of us have already left as Brodsky did. But he left for his global fame, to his Noble prize. They can do all that. But they can’t destroy us and they will be forgotten.

went to the Royal Mile and we went a video recording we uploaded today on facebook. We were just expressing out opinion about what happened, about what was going on in Russia in support of Kiril Serebrennikov. Our actor, Oleg Sidorchik, who is a political refugee himself, he said: “we all remember the story from Brodsky’s persecution. He got sentenced to five years in labour camp. And Anna Akhmatova, a great Russian poet, said: “what a biography they are making out for our ginger guy!” In a way, all those persecutors are making out the biographies of the creative people in one way or another. History is designed, so the names of the persecutors go into nothing and the names of the artists who are being persecuted will be remembered forever. So, those people, who are investigating into Kiril Serebrennikov’s practice, they will be forgotten. Whatever they achieve, whatever the result is, they will be forgotten. Nobody remembers the names of Brodsky’s persecutors, but everybody remembers Brodsky. Same will happen to Kiril Sreberennikov. They can steal a few years of his life, yes they can. They can force him to go abroad, into immigration. Yes, he will be able to be a successful director in any country in Europe. He is a successful director in Europe. He already had very successful productions in Germany, and he could move there forever. People can leave, some of us have already left as Brodsky did. But he left for his global fame, to his Noble prize. They can do all that. But they can’t destroy us and they will be forgotten.

Do you think that the censorship, in the form that it exists now… it’s obviously not Stalinist purges, but it’s the kind of situation that inflicts a lot of self-censorship, because people understandably don’t want to be made uncomfortable, people don’t want years of their life stolen. Do you think this kind of censorship inflicts silence or do you think it fosters creativity, like the censorship in the Soviet Union did in a way?

This censorship is a heritage from the Soviet period. The generation after Stalin, they’ve been silenced. They had to pick very thoroughly what they were saying and where they were saying it. The next generation still remembered that way of life. Of course, right now people in Russia are very careful about what they say, what they make shows about, what they write about. The government will not send you to prison directly for what you do or say. However, there are signals the government send us, for instance like with Kiril Serebrennikov. It’s a signal to the entire cultural layer, the artistic people in Russia: you could be the next one, any of you, chosen randomly, could be the next victim. Kiril Serebrennikov was not doing anything special, he was doing what everyone does. His theatre company was forced into a corrupted and criminalised system of usage of governmental grants. The system is designed so that it’s absolutely unclear. Anyone can be taken into an investigation for the way they used a government grant, because there is always some kind of an administrative mistake. Anyone could be chosen and persecuted. So think what you are saying, think what you are doing because if not punished immediately you could be punished for it one day. And people try to watch themselves. Also there is a very powerful orthodox, moral influence in the Russian society right now. If you are making a production that somebody doesn’t like because of their orthodox religious views they can make a demonstration in front of the theatre trying to force the government to look into the production, because it insults some religious feelings, they say. Which is not true, because in my opinion, in my honest opinion, true religious feelings can’t be insulted. If there is a religious feeling, it belongs to the person. That’s a powerful factor as well in Russia. So yes, censorship, self-censorship is a big problem. I feel that influence from my parents, for example. When I do something… And they live in Russia, and they will sometimes call me and say “Don’t. Just shut up.”. And I ask “What have I been doing that I should shut up?” and they say “You don’t understand”. And I say “Yes I do, that’s why I’ve been living in the United Kingdom”. I did understand why I was leaving the country. In order to be able to do what I want to do, what I decide to do and say what I decide to say.

We mentioned audience reaction, and the orthodox audience. What have the audience reactions to Brodsky Station been like?

There are a few roads of thinking. Some people don’t understand anything and they are lost. It’s quite understandable. But when they get out and they admit that they are lost, they start asking questions. I’m always there after the show to talk about it if they want to. Some people just leave, and some people cry. But those ones who want to talk, they ask you questions. And the decision they make is to go home and go through a couple of Brodsky’s poems, which is my direct intention: to encourage people who had no clue who Joseph Brodsky was to come and read a bit more, to raise their awareness. They start asking questions, they start being curious, which is great. Some people, who know who Joseph Brodsky was, they do understand the story and they get into what I’ve been trying to tell. And then there is another kind of reaction. There is a perception of it as an abstract piece of theatre, an abstract idea and they build up their own understanding of what was going on. I’ve heard at least 20 different stories of what was going on, on top of what I was doing and I’m always keen to listen to another one. It’s always fascinating when someone builds their own theory, their own plot. There are a few layers to Brodsky  Station. That’s what I learned from my teacher, Roman Viktyuk. That’s what he taught us: everyone who comes to your production should get something. There is a multi-layered cake in Russia, Napoleon Cake [at this point I nod enthusiastically, because I like that cake, but in case you have no idea what it is here is a picture]. It has a multitude of layers and there is a multitude of layers in Brodsky station as well: for those who know about Brodsky, for those who like abstract theatre, for those who don’t know anything about these and still can tell a story, for those who are into the visual part of the production. Everyone can get something from it, that’s what I was trying to achieve.

Station. That’s what I learned from my teacher, Roman Viktyuk. That’s what he taught us: everyone who comes to your production should get something. There is a multi-layered cake in Russia, Napoleon Cake [at this point I nod enthusiastically, because I like that cake, but in case you have no idea what it is here is a picture]. It has a multitude of layers and there is a multitude of layers in Brodsky station as well: for those who know about Brodsky, for those who like abstract theatre, for those who don’t know anything about these and still can tell a story, for those who are into the visual part of the production. Everyone can get something from it, that’s what I was trying to achieve.

Let’s talk specifically about the Russian audience. Do you think that the subjects that, in Russia, in theatre get negative feedback form the audience (and I mean something radical, like what happened to Kulyabin’s production of Tannhauser), do you think those reactions are triggered by the same subjects that the government tries to restrict from being spoken of?

Well look, the government doesn’t do anything directly regarding theatre. They do not forbid anything. It’s not the Soviet Union anymore, it’s much trickier and it’s much more serious in a way. Back in the Soviet Union, when the committee was coming from the communist party in order to watch a preview of the production and they were delivering their opinions on whether it will go on stage or not it was funny. I do remember the stories from that time, and it was fun. The practitioners were always putting things in, which would be easily spotted, like blue rabbits, and the bigger things would then not be touched. They knew how to trick those commissions. And right now there is no commission, there is no direct governmental involvement. There are some powers that can arrange gossip around this. They operate the social opinions about the productions. That’s the scariest thing. They arrange media campaigns around shows, they use smarter ways. Because smarter people, in a way, are holding the power in Russia now. Much smarter than those who were holding the power in 1980’s, for example. I believe those reactions from the audience are not necessarily the real reactions. Those who express their opinions on social networks very often have not seen the productions they talk about. They react without having any knowledge of the subject. They were told “this will offend your religious feelings” or “this will offend your morals”. They’ve been influenced by someone’s opinion, and that opinion has been dictated by qualified opinion makers, who follow orders. Sometimes it’s related to the political subjects, sometimes it’s related to financial reasons and I would not be sure what is worse, political or financial. So there are some powers around shows that were cancelled, that have been scandalised, that got a wave of negative comments. There is always someone, some power behind this. There are no direct closures. Almost no direct closures from the ministry of culture. That happens very rarely. To forbid something directly, that’s very rare.

Why do you think it’s so easy to create this official line of thinking to influence people’s opinions?

It’s a heritage from the Soviet times. The education system is designed so that the students in the school are trained to remember multiple facts, but not to make any conclusions. I’ve been surprised that in the UK in primary schools and secondary schools, on all levels of the education system students are encouraged, first and foremost, to form an opinion, to reflect on the subject, to write essays, to get involved in discussions. In the Soviet Union and moving forward to the Russian schools students are always learning a lot of facts by heart, they have to show the knowledge of facts but they are not trained to express their opinions. And that’s the reason grownups are not trained to make their own opinions. It’s done on purpose of course, because the political situation has not changed since then. The political powers need an electorate that does not think too much. It must be easy to manipulate it.

As you said, there are no official theatre closures, censorship does not officially exist, theatre productions are cancelled because the audience is offended by them, theatres are made to close not for their political ideas, but because the space does not meet health and safety requirements, Serebrennikov is on trial not for his shows, but for financial embezzlement. With all of that in mind, what does a Russian theatre director need to stage a play about to guarantee the negative attention of government authorities?

There is no recipe. As I said, almost anyone who is involved in making theatre will end up using governmental grants. When you are using it, when you are in a relationship with officials (and you must be if you are running a large theatre), you are under the risk of being the next. You could express an opinion in a private conversation, which will get to someone who is really vulnerable, who is sensitive and who is able to use their influence and say “I heard you were talking about this, I’ve heard you were making fun of that, you were making the wrong kind of friendships” and then through you someone else could be punished. You never know of all the lines that are going from you to someone else. There is no recipe. Whatever you’ve been doing, you could be doing something wrong even if you don’t know about it. You can’t self-censor every conversation, every relationship around you in order to be absolutely safe. There is no way to be safe if you are doing something. The best way to be safe is not to do anything at all. Don’t use the government money, stay home, watch TV – this is the safest way of existence. If you are not happy with this, if you are a little bit different and want to achieve something, you are under a threat at all times.

Obviously other art forms are subject to all this as well, but would you not agree that theatre occupies a rather specific niche? To me, it almost seems very strange that there has been so much focus on theatre. Why has that happened in the past few years?

Theatre is becoming a little bit more than a theatre. It’s not just a place where there is a stage, and there are plays, where you can watch Shakespeare and Chekhov. For instance, Serebrennikov has been running Gogol Centre, which is a real Centre, a Centre for the younger generation of people. It was a Centre where people gathered together for opposition protests. Serebrennikov attracted a certain kind of audience by his productions, exhibitions, the space he created: a cultural place for meetings and discussions. Gogol Centre used a variety of media to achieve that kind of atmosphere. Unfortunately, theatre was the keeper of the keys for a very long period of human history. That was the only power, only media. The majority of people were unable to read or did not have access to books through the majority of human history. There were no newspapers, no TV of course, but there was theatre and it has not changed the world. So theatre on its own, as we understand from history, is not that powerful. When it’s attracting other powers, connecting to new media and picking up quickly what’s on the top of the social mind making, then it becomes an influence. Theatre plus something else. That’s why I’m trying to reach to the audience through all the visual, social routes they are used to in their everyday life. I believe this is the real power, when you are on the top of the wave of the way in which society consumes information. That’s the only way to really be powerful. Not theatre on its own, but theatre and something else.

You can find out more about Konstantin’s theatre company 247 here

All images used in the article are taken from here is copyrighted by K.Y. Stanley Lin. 2016.